Article by Tony Reinke, Senior writer, desiringGod.org

Article by Tony Reinke, Senior writer, desiringGod.org

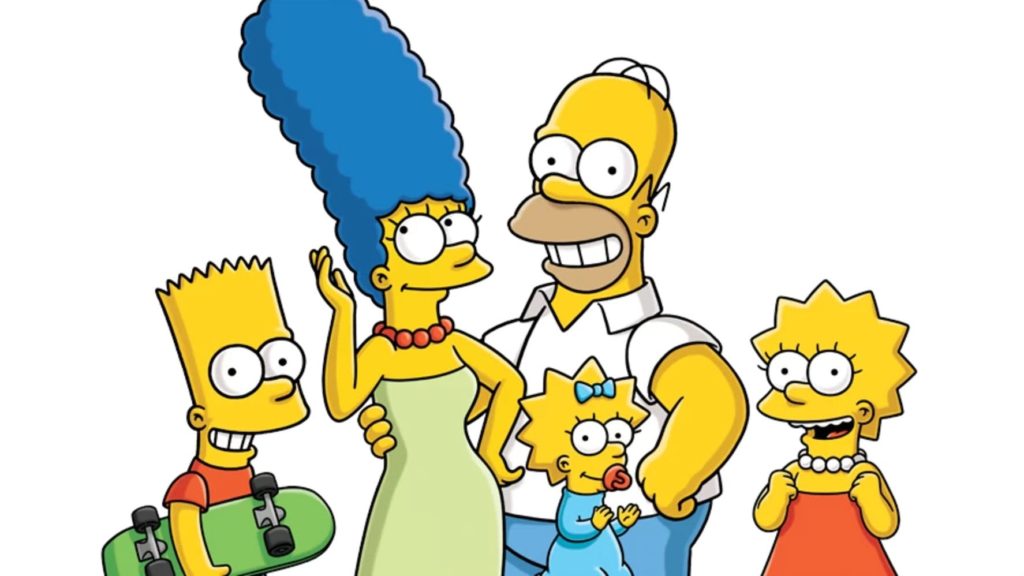

My generation was raised on The Simpsons.

The popular cartoon is postmodern TV at its finest: liberated from prolonged storylines, a series of jests sprinkled in every fifteen seconds (to capture anyone who just tuned in), often self-referencial sneers, a show loaded with subtle and overt cultural references, thick with irony, sarcasm, and inside jokes — a decades-long art form good at pointing out cultural anxieties, but challenged to celebrate community, truth, or beauty.

“I think The Simpsons is important art,” novelist David Foster Wallace said in an interview. But “on the other hand, it’s also — in my opinion — relentlessly corrosive to the soul, and everything is parodied, and everything’s ridiculous. Maybe I’m old, but for my part I can be steeped in about an hour of it, and then I have to walk away and look at a flower or something.”

It wasn’t just The Simpsons, but a whole generation of entertainment given to parody and irony and sarcasm, and it leaves us with a sense of something less human, less likely to encourage us to do what Wallace did — to turn it off in favor of natural beauty.

Letterman

This postmodern sarcasm seeped into the pop sitcoms and into late-night TV, as in the case of The Late Show with David Letterman.

Wallace explored this trend in his collection of short stories (Girl with Curious Hair), in a short story to imagine an actress getting groomed by her publicist and husband before appearing on The Late Show, a cultural staple of nighttime TV between 1993 and 2015.

“It’s easier to post wit and sarcasm and biting criticism online. The hard thing is to post sincere truth.”

The key for the actress’s successful interview was bound up with her poker face. It’s best if she was a little jaded. A little distant. Bored. Not insincere, just “not-sincere.” The key: “Appear the way Letterman appears on Letterman. . . . Laugh in a way that’s somehow deadpan. Act as if you knew from birth that everything is clichéd and hyped and empty and absurd. That’s just where the fun is.” Reflect his sardonic outlook on all of life.

This observation resonates with what I know of Letterman, as well as with what I know of the postmodern American entertainment culture of my youth. The age of sarcasm is the age of the lazy-eyed, smart-aleck comedian who wants you to know he’s playing a character dumber than himself (Bill Murray and Saturday Night Live). Mockery thrived in the derisive contra-family dramas (Simpsons), in the snark-at-every-life-situation form of faux-friendships (Seinfeld), in the cynical contra-talk shows (Letterman), and then later in the mistrust-everything-I-say, contra-news programs (Colbert).

Said Wallace, the 1990s were a time of “postmodern irony, hip cynicism, a hatred that winks and nudges you and pretends it’s just kidding.”

Cynical of Cynicism

Does satire work? Does it change anything? On one side of the argument, journalist Malcolm Gladwell recently attempted to argue that the more we laugh at something, the less persuasive that thing is for changing minds (“The Satire Paradox”). Satire makes for laughs but cannot change minds, at least not for unified social change. But this conclusion seems defective.

“Letterman’s ‘irony’ was in fact a passionate response against phoniness,” writes James Poniewozik of Time Magazine. Yes — and it worked. Sarcasm was the chosen tool of a generation of entertainers to poke holes in what they perceived to be a phony, over-idealized picture of life that dominated American entertainment in the 1950s. The polished formality of the tightly scripted news, the straight-collared conversations, the seriousness, the sincerity, the wholesome TV family got capsized by a generation of sarcastic entertainment — the Lettermans, Simpsons, and SNLs.

“Sarcasm is a free-swinging wrecking ball. It cannot construct.”

Satire’s most potent work is in exposing phony facades. But it cannot accomplish anything more important, and there’s the problem, as Wallace explained in a 1997 radio interview: “Irony and sarcasm are fantastic for exploding hypocrisy and exposing what’s wrong in extant values. They are notably less good in erecting replacement values or coming close to the truth.”

Sarcasm is a free-swinging wrecking ball. It cannot construct.

So what happens when mocking sarcasm lives past its use and becomes the tone of a generation? Wallace explains. “What’s been passed down from the postmodern heyday is sarcasm, cynicism, a manic ennui, suspicion of all authority, suspicion of all constraints on conduct, and a terrible penchant for ironic diagnosis of unpleasantness, instead of an ambition not just to diagnose and ridicule but to redeem. You’ve got to understand that this stuff has permeated the culture. It’s become our language; we’re so in it we don’t even see that it’s one perspective, one among many possible ways of seeing. Postmodern irony’s become our environment.”

The Ghost of Sarcasm

Sarcasm is still in the groundwater of our entertainment, in every drink, and we can no longer smell its pungent stench. This is one reason why TV inherently favors political newcomers, and resists incumbents. Satire takes down authority structures and establishments. And the acerbic wit and irony that may have exposed hypocrisy in a previous generation continues living, with an undiminishing life of its own. We’re trapped in it. Sarcasm becomes a tyranny we cannot escape.

Sarcasm is ghostly. It defies all resistance. You try to push against irony and your arms flail in the mirage. Even our popular ads become satire. And as satire, they evade criticism by absorbing all criticism. So for example, LeBron James will never tell you to drink Sprite, because he knows we’re all guarded against propaganda. Satirically he makes fun of his own commercials, and by doing this, he and Sprite evade critical thought. If I message LeBron to say that Squirt is clearly superior to Sprite, he could respond and say he never said it was, and never said I should drink one or the other. And he’d be right.

“Nothing is more countercultural to snark-culture than sincerity.”

There’s the irony. Any ad you cannot criticize is an ad to be received. To this end, self-satirizing ads multiply like spring rabbits. “Do you see we’re making an ad inside this ad? Get it? Get it!?”

As nauseatingly as the “inside joke” ads have become, the tactic is a brilliant invention of our admen and adwomen to disarm buyers. Advertisers say to us, “We see you seeing us try to sell you things, and let’s laugh at the whole thing together!” Sharing an inside joke is the best way to capture a defensive ad audience.

But even beyond ads, the spirit of the sarcasm age thrives in the memes of social media, in anti-institutional hashtagism that can tear away smokescreens and hypocrisy, take down authorities and demonize institutions. Witty sarcasm on social media defies criticism. Nor is it able to draw consensus and construct newer, and more stable, social structures.

Ruined for Beauty

The sarcasm culture, deadpanned in the eyes, doesn’t stop corroding society. It’s like dry rot eating away a culture’s weight bearing timber.

Unchecked, the sarcastic man’s affections become so corroded, his eyes so deadpan, so I-know-more-than-you, that those same eyes cannot weep at created beauty, let alone see it. He cannot submit himself to truth. He becomes cynical for all that is redemptive. He falls prey to the tyranny of sarcasm. He cannot criticize the tyranny of the jaded sarcasm itself.

It is true, irony is a good way to poke fun at yourself. Perhaps Christians can take some cues from Ned Flanders, the most famously satirized evangelical. Like the satirical voice from a whirlwind aimed at Job, irony has a useful place in pushing back cultural idols and evangelical presumptions. But sarcasm aimed to subvert others should be taken in small doses.

Sarcasm Culture and Redemptive Hope

In a sarcasm culture, we must renew the call for redemptive Christian sincerity. Yes, it’s easier to post wit and sarcasm and biting criticism online. The hard thing is to post sincere truth and to put yourself in a vulnerable place before the eyes of a ridicule culture.

In his longest novel, one of Wallaces’s fictional characters seeks to evade loneliness — “the great transcendent horror” — by becoming so hip and cool and cynical about life to be included among his peers. But the end result of the Simpsons and Letterman was not to foster a place of belonging or for true friendship, but isolation — a world where “hip cynical transcendence of sentiment is really some kind of fear of being really human,” and in evading what is human, we become disingenuous, incapable of the self-disclosure required of community. We’re left with random Seinfeld-like connections with others, with zero depth and with nothing of significance to offer one another but another punchline jeer to distract each other from our troubles.

Our media shape us in one profound way that’s hard to shake. As Wallace once said, “All U.S. irony is based on an implicit ‘I don’t really mean what I’m saying.’”

And there’s the problem.

More Powerful Than Sarcasm

Nothing is more countercultural to snark-culture than sincerity. And nothing is more human than sincerity, for only with sincerity can you weep at truth and beauty. For Christians, deadpanned in the eyes is not an option. For “those who sow in tears shall reap with shouts of joy!” (Psalm 126:5).

“Jesus died so that we could be sincere with the world, sincere with ourselves, and sincere with one another.”

Deep sincerity — tear-filled sincerity — is an essential marker of spiritual health and the aliveness of our affections, and critical to our gospel mission. The apostle Paul’s ministry is substantiated by its sincere love: “As servants of God we commend ourselves in every way: by . . . genuine love” (2 Corinthians 6:4–6). He calls us to an earnest trust in God as he celebrates Timothy’s “sincere faith” (2 Timothy 1:5). It is in this sincere faith that we all must express sincere love for others: “The aim of our charge is love that issues from a pure heart and a good conscience and a sincere faith” (1 Timothy 1:5; see also Romans 12:9; 1 Peter 1:22).

And even if ridiculers turn out to hate knowledge, we live under the authority of divine truth in sincerity, as James 3:17 says, “But the wisdom from above is first pure, then peaceable, gentle, open to reason, full of mercy and good fruits, impartial and sincere.”

Questions to Ask

So who are we, and who will we be in this culture? Sarcastic or sincere? Scoffers or builders? Known by our ridiculing barbs or by our redemptive hopes? Are we offering one another a deadpanned face, or do our expressions express love, interest, and self-giving sincerity?

These may seem like theoretical questions, but they are real questions, ones probably already answered in the archive of our social media feeds and in our most liked and retweeted memes.

Christians in the age of snark have beauties to relish far beyond the beauties of a single rose. We have the beautiful Rose of Sharon, the beauty of a stunning Savior who died so that we could be sincere with the world, sincere with ourselves, and sincere with one another — that is, to be fully human.

We are free in Christ to enjoy beauty, to tweet truth, and to be vulnerable, because we have died to the base things of this world and the dominant sarcasm culture of America’s media, and have been made alive with him to truth, beauty, and sincerity again.

Tony Reinke (@tonyreinke) is senior writer for Desiring God and author of 12 Ways Your Phone Is Changing You (2017), John Newton on the Christian Life (2015), and Lit! A Christian Guide to Reading Books (2011). He hosts the Ask Pastor John podcast and lives in the Twin Cities with his wife and three children.